Getting Loopy on the West Ridge of White Mountain

The sun has just dipped below the ridge of the horseshoe-shaped glacial moraine. Couches ought not to be this comfortable—it skews judgment. Weather forecasters anticipate a low-pressure system will soon bring the year’s first snowfall. One seasonal window making way for another. My list of remaining objectives is long. “I really should to make the most of this,” I think as I sink into the couch, mildly overwhelmed by the possibilities.

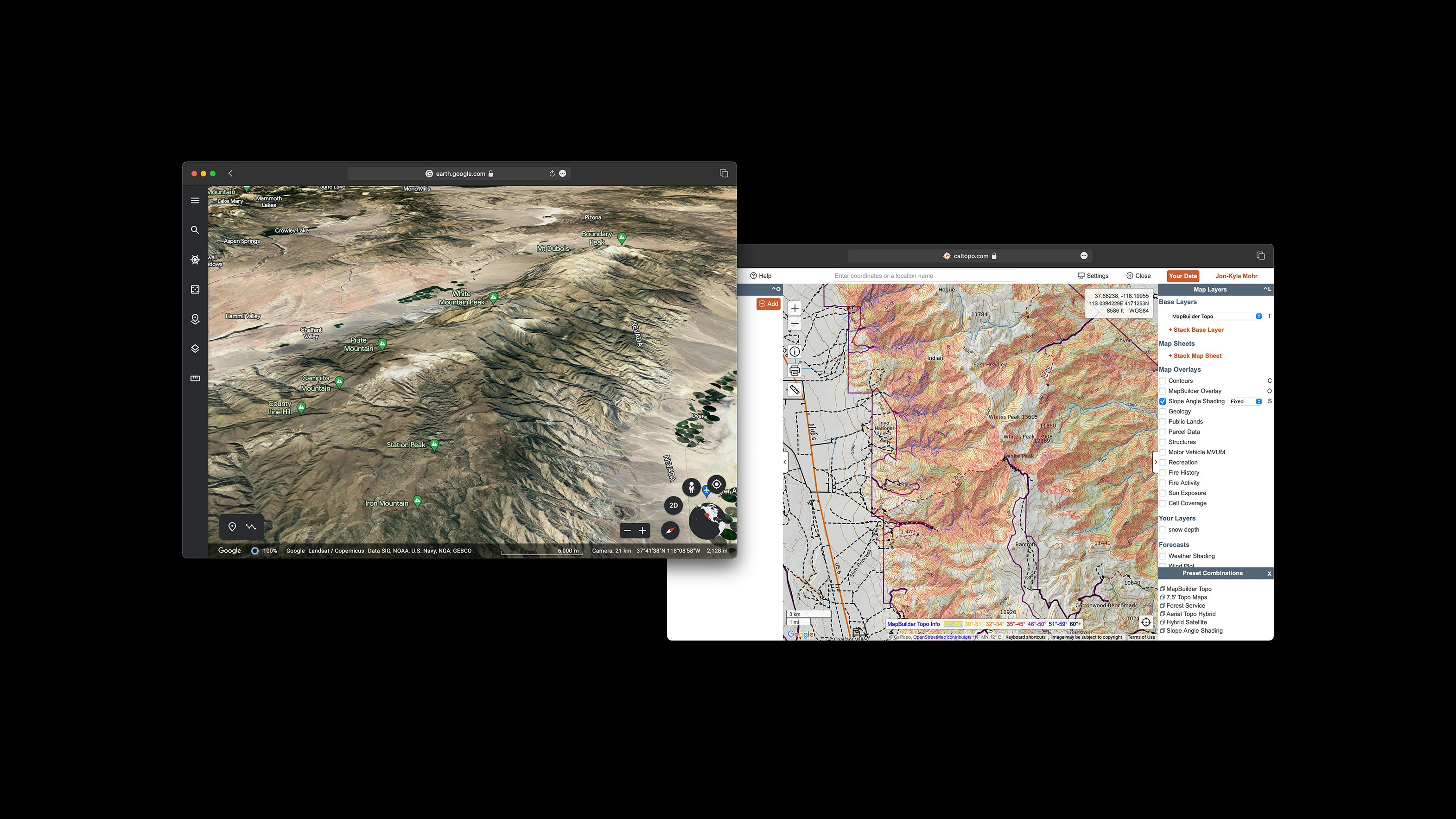

Two tabs are open on the screen: Google Earth and CalTopo. Although there are many similar tools out there, these are my trusted friends for getting to know expansive areas of terrain good for cross-country travel. Having a solid understanding of what’s out there is a good idea.

At times, there is a dissonance between leaving the digital realm of the browser and stepping onto solid ground. Striking a compromise between thorough preparation and embracing serendipity is a balancing act.

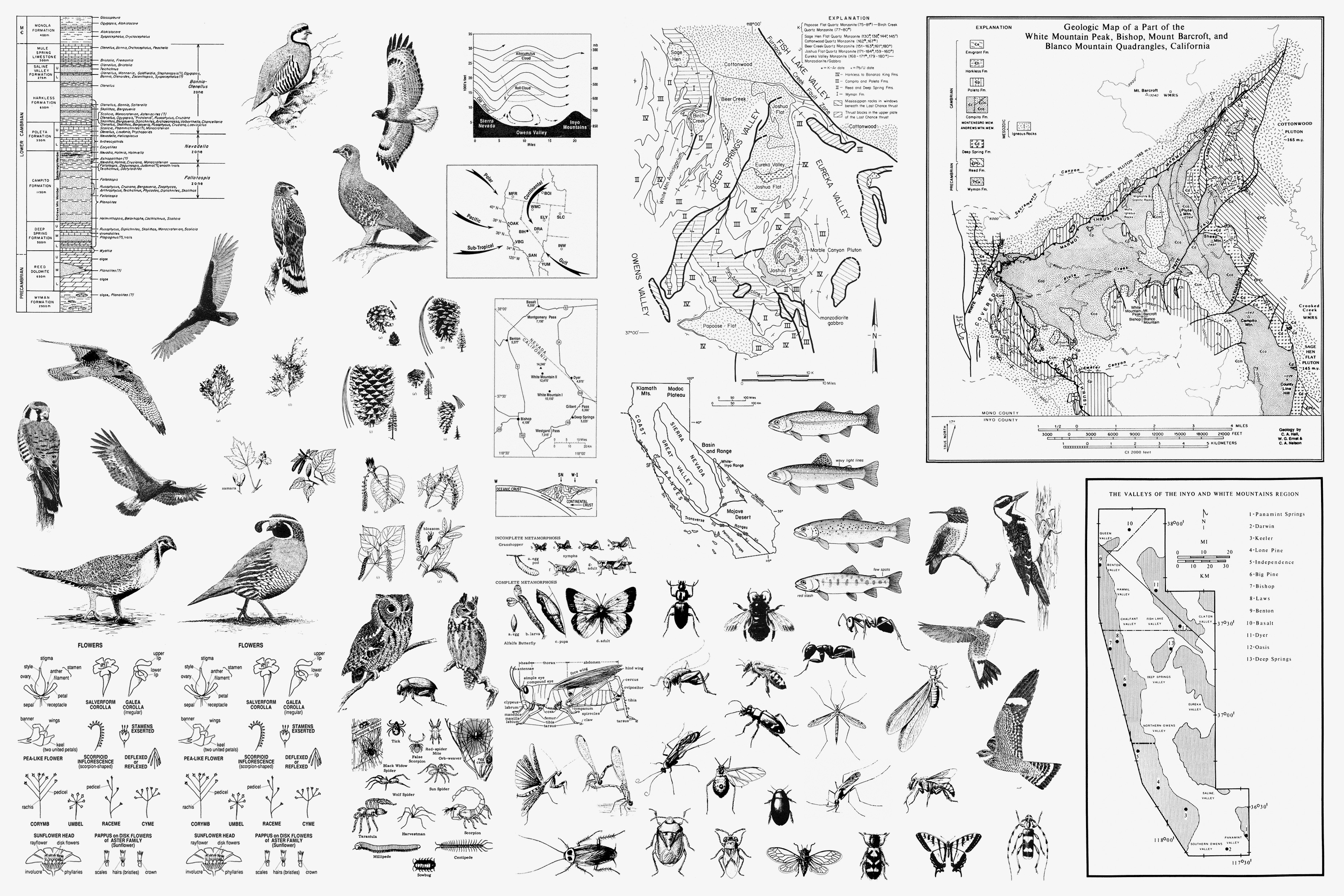

While zooming at a dizzying pace of hundreds of miles per drag, a particular peak captures my curiosity. White Mountain, one of only two California peaks exceeding 14,000 feet outside the Sierra Nevada, is the eponymous summit of the White Mountains. This fault-block range runs parallel to the Sierra at the northern end of Owens Valley and is known for its sub-alpine forests filled with gnarled and twisted bristlecone pines.

Methuselah, a bristlecone whose precise location remains undisclosed to the public, stands as the oldest living tree on Earth at some ~4,850 years.

For most heading to White Mountain peak, the paved road terminates at a visitor center, giving way to a dirt path. This route is characterized by sharp and protruding rocks, notorious for puncturing the tires of unlucky travelers. The journey on foot begins at a gate designated for the Barcroft Research Center and Field Station one passes en route to the summit.

Perched at an elevation of 12,470 feet, Barcroft Station ranks among the highest research stations in North America. The facility is dedicated to numerous studies examining the physiological effects of altitude on the surrounding ecology, captured in an endearing and quirky film produced by the University of California Television department.

A visit to Barcroft Station will have to wait, as my chosen path will not lead me there. I am reminded of a friend, Ariana, whom I met on the Pacific Crest Trail back in 2019. We leapfrogged for a few days in the Sierra, navigating unusually large river crossings amid the annual "big thaw" during a year of exceptional snowfall.

After her time on the PCT, Ariana pursued several ambitious objectives, including establishing the unsupported female FKT (Fastest Known Time) for the west ridge of White Mountain at a very solid 12 hours and 8 minutes. This required an ascent (and descent) of 11,806 feet over a distance of 20.87 miles.

Ariana's achievement is monumental, and while I wasn’t looking to establishing an FKT myself, the route got me thinking. White Mountain looms over Bishop and commands the horizon while heading up Sherwin Grade towards my home in June Lake. The peak has long been on my list, and the idea of an exceptional ascent became my overriding fixation.

Of course, there’s always room to up the ante…

The FKTs were established as out-and-backs, sticking to the same route along the ridge for both ascent and descent. Fine, but I try to avoid out-and-backs. Shaping a loop that traverses new terrain helps to maintains interest with fresh perspectives along the way.

As I examine adjacent contours to White, searching for hints, the west ridge of Barcroft grows enticing. Just four miles to the south by way of a gently undulating alpine plateau, the slope angle shading suggests smooth passage devoid of unexpected obstacles. My interest isn’t the total mileage or elevation gain; it’s all about the line.

As evening advances, the move is to sleep soundly in bed, rising early to make the hour-long drive to the starting point. After all, the privilege of sleeping in one’s own bed in a real room is a key advantage of residing in the Eastern Sierra, right?

Alarm set for 3:30am. Pack is good to go. Lights out.

My second-generation Forester seemed somewhat spooked by the sizable rocks strewn about. I often experience greater apprehension when driving approaches than while scrambling. A punctured tire in this location would be… annoying. Ariana began her FKT at the Champion Spark Plug Mine plaque to circumvent these hazards, and to give the route extra aesthetic appeal. I agree her! Still, I proceeded farther and parked alongside an offshoot road, feeling little guilt given the extra mileage of my loop.

Standing at the northern end of the Owens Valley, what some call the deepest valley, the towering summit of White looms somewhere approximately 10,000 feet above me—about twice the depth of the Grand Canyon. As the headlamp's red glow casts shadows on the sage, the first light of dawn subtly illuminates the stratosphere's upper reaches. Time to start moving.

Gradually, Chalfant Valley recedes with each step taken. A small weather station signals the end of the unexpectedly steep and rutted dirt road, and I am shocked that any vehicle with four wheels could navigate such terrain.

Glancing over my shoulder, I observe the granite crest of the Sierra shimmering in shades of pink and gold, as the alpenglow gradually descends towards the foothills. I pause to enjoy a Snickers bar, appreciating these moments that evoke a sense of planetary scale and connection to a greater whole transcending daily existence.

Gentle inclines yield to expanses of scree and talus. My progress slows, the terrain becoming uncooperative with lousy footholds that cause me to slide backward with each step. This might bother someone more focused. I find myself too absorbed in the kaleidoscope of colors and textures beneath my feet to get too frustrated.

Approaching mile six, the ridge gradually transforms into a serrated knife-edge. On the Yosemite scale, it qualifies as Class 3, with a dose of exposure. “Moderate scrambling on steep, rocky terrain that requires handholds for upward movement and safety.” After descending a series of ledges and cracks, I find myself cliffed out, suspended fifteen feet above the ground. While the route might go, a slip or sprain here would be a significant setback. This sequence repeats once or twice more before I eventually locate a ramp on the north side of the ridge, allowing me to traverse around the more vertical areas.

Living at 7,500 feet in June Lake has undoubtedly been beneficial for my lungs, and throughout the day, they've shown no signs of strain. However, during this final ascent of 1,000 feet to reach 14,000 feet, the lack of oxygen becomes my central focus.

A little scrambling is all that remains, and with a burst of effort, the summit is attained. From this vantage point, the vastness of Nevada sprawls out beneath me, no longer occluded by the spine of the White Mountains. I take in the panorama with several full rotations, before settling onto an ergonomic and comfortable rock against my back. It's time to enjoy the aluminum-wrapped pizza I've brought along—there's nothing quite like cold pizza in the backcountry.

I’m in the middle of a solid zone out session—you know, the kind where you dilate your peripheral vision while staring at infinity and eat cold pizza—when someone approaches. “Hey!” He hands me a beer. Quite the gesture, considering he just carried this weight 15 miles and 3,360 feet from the gate at Barcroft. “Wow, thanks!” Perfect pizza pairing.

He goes by “Whinchester.” Living nearly 10,000 feet below us in the Chalfant Valley, he entertains me with stories from his last visit, where a blown tire on the road in turned a day hike into a multi-day adventure. “You see this jacket?” he asked pointing to his azure outerwear. “First Gore-Tex jacket Patagonia ever made, original. Still use it.”

Like me, he had a long walk back to the car. After lingering for a while, I sign the trail register and soon catch up to him. A few more minutes of chatting, and then it's time to run the trail towards the next objective—Barcroft Peak.

Looking at the road leading from the summit of White and stretching through the unending rolling hills, my eyes trace the path until it terminates at a saddle. There, Barcroft Station awaits, with Barcroft Peak lying just to the west. Running at a slight downhill grade feels refreshing after a day spent slogging up talus and scree.

The sun is sinking low on the horizon, a line defined by the spine of the Mammoth Crest. White Mountain, located to the north, reflects the last beams of direct sun, its rhyolites and occasional andesites aglow in the fading light.

As I make my way towards Barcroft’s prominence, the gradual descent eases into a relatively modest climb. Though it would be great to see the sun fully set from the summit, time is of the essence and I'm cutting it very close. I pick up my pace and just barely reach the top with mere seconds to spare. As I turn to look behind me, the peak throws a triangular shadow to the horizon across the Silver Peak Range of Nevada’s Esmeralda County.

The light show comes to an end and the trail register pops open, which doesn't see much action. I'm happy to contribute another scribble. With the sun now gone, the temperature drops, and gusts of wind begin sweeping across the alpine plain. My hands are freezing, and my signature is entirely illegible. Warming up becomes the priority, and it's time to get moving on the second half of the loop.

While there was plenty of useful beta for the ascent of White's west ridge, I'm flying blind on the descent from Bancroft. It's a relatively obscure route compared to nearby White, but its neglect contributes to the aesthetic appeal.

The descent starts on a wide slope that narrows to a choke point as it follows the ridge defined by steep drops. The slope-angle resolution here is low enough to smoothly interpolate over big features. Similarly, Google Earth’s 3D view smooths out large boulders and even entire towers. While you may have a good idea of what’s ahead, a “first descent” of this scale at night gets the blood flowing when considering possible unknowns.

As eyes adjust, the headlamp switches back to red light. This greatly aids in preserving vision by preventing unnecessary pupil dilation. The lights of Bishop serve as a reference point, indicating the diminishing distance between the current location and the high desert floor. My watch dies; consequently, I begin tracking on my phone.

Fortunately, the terrain remains easy to traverse, as it is primarily solid and does not closely resemble the unstable parallel ridge of White; this can be ascribed to the sagebrush that I am rapidly sidestepping to the left and right.

It has been nearly 14 hours since I began. The consistent cadence of my steps lulls me into a delirium as I focus only a few feet ahead at a time while descending several thousand feet. Suddenly, I am startled out of my trance by a lone tree, the first of many that gradually increase in density over the next few hundred feet in elevation. The choke points, which had been an earlier concern, prove to be mere blips as I maintain my position on the ridge. Progress is being made.

With only several hundred feet remaining beneath me, my plan is to leave the ridge to the north and descend scree down to a dirt road. However, one thing a topographical map cannot prepare you for is an angry pack of dogs in the middle of the night. I am unsure of their location and their exact number, but they do not sound happy. I hear voices in the distance, whom I assume are trying to determine the cause of the dogs' agitation. Not wanting to find out if the owners' demeanor matches that of the dogs, I continue to follow the ridge.

Eventually, a discernible trail emerges to follow, while the sounds of the dogs seem to recede to the right, gradually growing fainter. Just like that, a noticeable flatness appears, marking the end of the ridge descent off Barcroft. It is cause for celebration, indeed, but only for a fleeting moment as the next challenge promptly presents itself.

The intended road to take is obstructed by a gate, an extension of a property line running directly perpendicular to my ideal course. Unwilling to risk trespassing in the dead of night with a pack of irate dogs lurking somewhere in the darkness, I trace the property line while consulting the map to determine my options. After what feels like an eternity, I reach an intersection with another dirt road, devoid of any gates and leading toward my car.

Eventually the road is left behind, traversing undulating, deep washes. I am startled by a pair of eyes that, upon closer inspection, belong to a cow. By now, this detour has added a minimum of three to four miles to an already full on day.

Another glint from my headlamp captures my attention. As I approach cautiously, the source reveals itself to be the taillights of my car, my tired eyes at this point playing tricks and challenging my ability to gauge distance accurately.

Within a few minutes, I find myself where it all began, a testament to a good slog; back at my car, in the dark.